There’s one speech error that I’m noticing crop up more and more.

“Hey!” He said.

“What?” She answered.

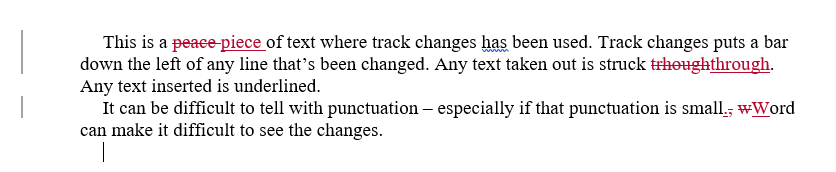

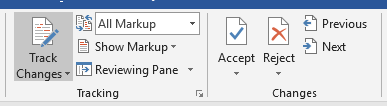

Sometimes it’s the fault of the software used, which will automatically capitalise the next letter following what’s normally terminal punctuation, in this case exclamation mark or question mark. If this is happening to you, investigate how to turn this off, as it’s more trouble than it’s worth.

The he said or she answered is the speech tag, to show who said the words. As such, it’s part of the original sentence, and shouldn’t be capitalised.

“Hello,” he said.

“It’s a lovely day,” she answered.

Just because the speech itself ends in terminal punctuation doesn’t mean it’s the end of the sentence.

And just as incorrect is:

“Hello.” He said.

“It’s a lovely day.” She answered.

Be careful when you add speech tags!

Of course, it’s also easy to go the other way:

“Hello,” he took a big sip of his coffee.

should be:

“Hello.” He took a big sip of his coffee.

Is the bit after the direct speech a complete sentence? Then start it with a capital letter, and make sure the speech ends in terminal punctuation – full stop, exclamation mark or question mark.

If it isn’t a complete sentence, then there’s no capital letter following, and the speech itself needs to end in a comma, exclamation mark or question mark.