The most important part of your book is the story, but when you’re producing a book for print there are other sections to consider as well. Please note that here I am considering novels only – non-fiction books are a completely different issue.

The front matter is everything that comes before the main story.

This must include:

- title page

- imprint page

It may also include any or all of these:

- half title

- dedication

- about the author

- praise/reviews

- list of previous works

- acknowledgements

- author’s note

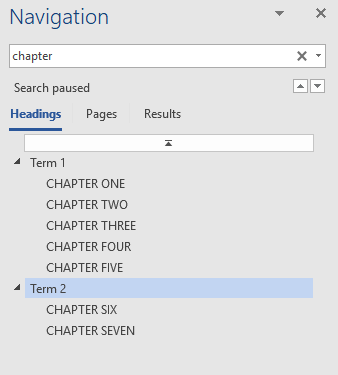

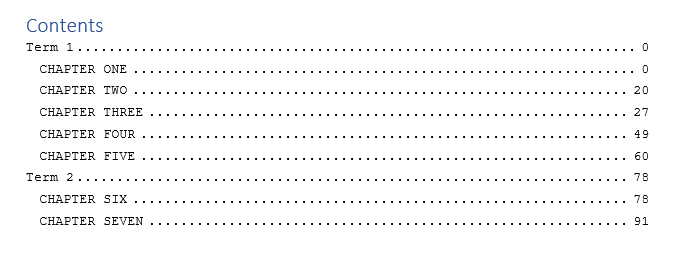

Fiction books do not usually include a table of contents.

Some of this content is necessary, while others are optional. And there are conventions as to whether the content appears on a recto (right-hand page) or verso (left-hand page).

The Title page consists of the title, any subtitle, author’s name (but without the word “by”) and maybe the publisher’s name/logo. The title page is always recto.

The imprint page contains information about the publisher, copyright declaration, any other legal declarations, information about the printer, any information about design etc. This is always verso, on the back of the title page.

The half title consists of the title of the book only, usually centred on the page. This dates from when printers would have stacks of books sitting around waiting for their covers, and they would need to be labelled so they could be identified easily! If a half title is included it is the very first page of the book, and therefore recto.

The Other Books section is most often included as a verso page, and this is often a good pair with the half title. This is a good opportunity to provide information such as the order of a series, or to direct your reader to other series you may have written.

The Dedication is usually recto, giving you the opportunity to dedicate your work prominently to someone special or who has played a part in the creation of the book.

The About the Author section may be at the very front of the book, as an alternative to the half-title. Alternatively, you may prefer to put it amongst the end matter.

Praise/reviews often appear before the title page if used. Again, this can provide an alternative to the half title for pairing with the Other Books page.

Author’s Note and Acknowledgements may both be included within front matter or back matter, but if they appear as front matter it is more common to start them on a recto.

All this means there may well be blank pages included in your front matter. This should be considered along with your printer’s requirements – if the printer prints in 16 page signatures, then your page count will made up to the next 16 count with blank pages if necessary. If the choice is between having extra front matter or extra blank pages at the back, I would choose the front matter. If the choice is between extra front matter or fewer pages and therefore lower cost, that might change the decision!

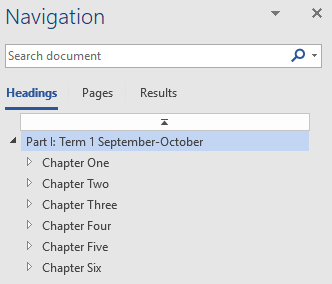

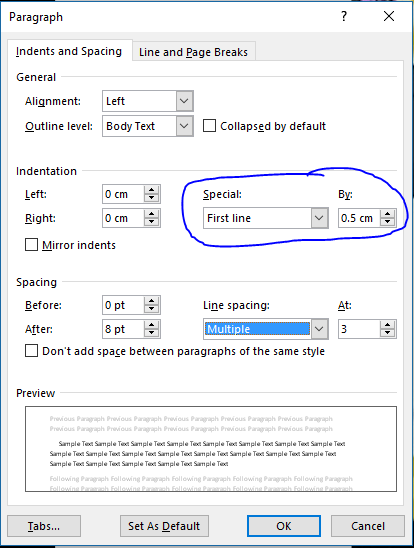

The main content of your book should always start on a recto. Some books follow the convention of starting every chapter on a recto, leaving the previous verso blank if needed, while others will start the chapter on whichever side of the page it falls naturally. Either way, the norm these days is to always start each chapter on a new page, with a large heading partway down and the text itself starting at about the 1/3 mark.

Why not pick up a few books from your bookshelf and take a look at the front matter? That will give you a feel for the standard layouts and content.