I’ve finished my novel! I have a complete, readable story. So now I knock together a cover, upload the cover and Word file to Amazon and hit publish, right?

Wrong.

Now the real work begins.

It’s really important to understand that there’s a continuum in writing. There isn’t any bad/good writing divide. There’s a whole range of qualities between barely readable and compelling writing. Just because you’ve completed a draft, and maybe a friend has enjoyed it, doesn’t mean it’s ready to publish. It means you have something you can work on and develop.

In this age where we can literally type “The End” on a draft and then have it for sale within minutes, some people are tempted to do just that. The result is often a barely readable mess, with spelling, punctuation and grammar issues, random tense changes and very odd, distracting formatting and a cover that screams Self Published!

If you just want people to read your work, then there are platforms where you can upload it and have a ready-made audience. In fanfiction particularly, writers can upload stories and be inundated with praise. That’s often not because of the writing, but because of the ideas they express about the characters people have already bonded with.

If you want people to pay for your work and feel so happy they’ve done so that they’ll tell others, then you need to put in a lot more investment – in terms of time, effort and usually cold, hard cash.

I can’t afford it, you might say. That’s where the traditional publishing market comes in. Find yourself a publisher, often via an agent, and they will invest in the writing for you, as long as they feel it’s good enough. Of course, they’ll take their share of the profit for doing so.

Failing that, you need to be prepared to put in the effort yourself. This means revising until you can’t see any way to improve it, asking beta readers to help, working on it some more, and then when you’ve taken it as far as you can, you enlist the professionals – the editors, the formatters, the proofreaders, the cover designers.

After all, the traditionally published writers expect to be put through such quality control, and they will be your rivals for sales. And you have not only your own reputation as a writer to protect, but the reputation of indie authors as a whole.

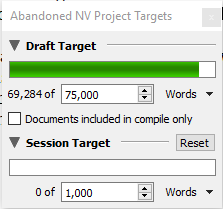

So now I have a full draft of my novel, I’ll be going back through to beef it up, and then seeking help, and I’ll be saving up for an editor, because even though I’ve studied writing and editing intensively, I know that I’m too close to it to edit my own work. And I’ll be making sure that what I do eventually publish will be the best I can make it, because I want my readers to want more, not to feel they’ve wasted their time and money on an inferior product.